Why Teams Are So Important in Business

Professional teams are a critical organizational unit across almost all industries, fields, and sectors. But the ingredients for effective teamwork are often not well understood, which can lead to poorly constructed teams. A large majority of employees say they don’t like working on teams, which usually reflects experiences with working in groups that lack the qualities of a true team.

In their book The Wisdom of Teams, McKinsey & Co consultants Jon Katzenbach and Douglas Smith describe five levels of teams. The first two – working groups and pseudo-teams – are at the bottom of the performance curve. In a working group, people coordinate their efforts but do not share common goals or a common purpose. In a pseudo-team, the team members do not share a focus on collective performance and are unwilling to take risks to strengthen the team. Katzenbach and Smith say this is the most dangerous type of team because participants often think they are part of a real team but fail to achieve optimal results.

In top teams, which Katzenbach and Smith call real teams and high performance teams, people are aligned under a common purpose and work together to achieve a common goal with interdependent effort. The members have complementary skills and are accountable to each other. Katzenbach and Smith define a team by its synergy, a collective effort that is greater than the sum of its individual parts.

Synergy derives from the idea that no individual can do everything perfectly; rather each person has a unique set of strengths and weaknesses. Teams compensate for these weaknesses by combining the right mix of people, so the strengths of some team members offset the weaknesses of others.

These strengths and weakness often fall into recognizable patterns among individuals, and these patterns are often termed roles. A team role, as defined by the influential British management theorist R. Meredith Belbin, is “a tendency to behave, contribute, and interrelate with others in a particular way.” You can broadly classify roles into two categories: formal and informal. Formal roles are positions with specific responsibilities (such as the leader) who are responsible for ensuring the team completes formal tasks. Informal roles, are those naturally adopted by team members based on how they interact with the world.

Synergy doesn’t arise spontaneously. When forming a team, you have to carefully consider what each person can offer. Selecting team members based on popularity, likeability, or friendship may result in not having the right people to play the necessary roles. Managers usually are clear on who should fill formal roles, but they more often struggle to choose people that can ensure a balance of informal roles.

Project Management Guide

Your one-stop shop for everything project management

Ready to get more out of your project management efforts? Visit our comprehensive project management guide for tips, best practices, and free resources to manage your work more effectively.

Britain’s Belbin Pioneers Team Role Theory

R. Meredith Belbin, the British management theorist whose seminal work on team roles in the 1970s and 1980s still shapes our understanding of team roles today, began developing his ideas when he was invited to study behavior of game participants in 1969.

The story begins at the Administrative Staff College at Henley-on-Thames, now Henley Business School, which administered a world-renowned course for high-performing managers. This course involved a business simulation, where the managers competed in teams to solve carefully constructed business problems designed to model real-world situations. Belbin, an academic, was asked to use this business simulation as the subject of a study into team behavior.

Belbin, who at this point had yet to develop a theory of teams, convened three other scholars to help him make sense of team performance in this business simulation. These were an anthropologist, an occupational psychologist, and a mathematician. They invited participants in the simulation to take a range of psychometric tests, most notably an assessment of high-level reasoning ability and a personality inventory. The scholars fully expected teams comprised of members with high intellect scores to outperform teams with lower intellect scores.

They were surprised by the results: when they assessed the teams’ performance, team intellect was not the ultimate predictor of team success. Instead, teams whose members played roles that were compatible with each other were more likely to be successful.

Belbin turned his attention to these team member roles, eventually defining eight distinct clusters of behavior that contributed to team performance. These eight behavior clusters became the original eight Belbin roles in 1981. In 1991, Belbin added a ninth role. The Belbin roles became the basis for a copyrighted behavior assessment called the Belbin Team Inventory, and variously referred to as the Belbin Self Perception Inventory (BSPI) and the Belbin Team Role Inventory (BTRI). The Belbin Team Inventory first appeared in Belbin’s 1981 book Management Teams: Why They Succeed or Fail. Although Belbin’s roles seem to be rooted in personality differences, Belbin contends the Belbin Team Inventory is not based on personality types, but on behavior tendencies.

The Belbin roles are the leading way to model and understand team behaviors. By selecting team members based on their natural Belbin roles, you can create more balanced teams. Also, a team’s understanding of the Belbin roles can lead to greater recognition of what each team member brings to the table and in turn decrease conflict due to a lack of understanding. Recognizing individual strengths and weaknesses is likely to improve synergy.

What Are Belbin Team Roles?

Belbin believed, “The types of behavior in which people engage are infinite. But the range of useful behaviors, which make an effective contribution to team performance, is finite.” These useful behaviors are the basis of the nine Belbin team roles.

One of Belbin’s most interesting observations was that useful behaviors, perhaps by virtue of the personality characteristics that underlie them, occur in recognizable clusters. On the flip side, he also identified patterns of negative or unhelpful behaviors that appear in conjunction with useful behaviors. Belbin called these non-useful behaviors “allowable weaknesses.” The helpful and unhelpful behavior tendencies are two sides of the same coin.

Here is a description of each of Belbin’s nine roles.

What Is a Shaper?

Shapers are high-energy problem-solvers who thrive under pressure. People look to them when the chips are down. Shapers enjoy a challenge, and they’re constantly pushing their teammates to improve. Even if there aren’t problems on the horizon, shapers direct their energies to ensure that their teammates don’t become complacent.

Since shapers like pushing the norms, they may have friction with teammates who prefer stability. They also tend to enjoy productive conflict, which doesn’t always go over well with the rest of the team.

Allowable Weaknesses: Shapers can instigate conflict and may at times be insensitive to other team members’ feelings.

What Is an Implementer?

Implementers are practically-minded people who excel at taking ideas off the page and into the real world. They’re goal oriented, which means they’re good at creating plans that turn concepts into results. Efficient and well organized, implementers are highly disciplined, and they thrive in consistency.

Implementers' fondness for consistency means they typically dislike change, especially if they see it as change for change’s sake and not to meet a viable end. As such, some team members may consider them narrow-minded.

Allowable Weaknesses: Implementers can be inflexible and slow to adapt to changes.

What Is a Completer Finisher?

Completer finishers are detail oriented and conscientious, the kind of people who take great pains to ensure the quality of their work and who double-check everything. They’re goal oriented, but they prioritize quality of work and goal specifications, including deadlines. They can be relied upon to please a project’s customers or stakeholders.

Completer finishers’ natural strengths come at some personal cost, since they tend not only to work conscientiously themselves but also pick up the slack for other team members who aren’t perfectionists.

Allowable Weaknesses: They can be prone to anxiety and stress and are loath to delegate.

What Is a Coordinator?

Coordinators are team leaders in the classical sense: they're natural organizers of people and delegators of tasks, and they’re good at building consensus and aligning a team towards its goals. These abilities come from their natural strengths of recognizing and communicating how individuals fit into the team, and they’re usually very likable people.

Allowable Weaknesses: Coordinators can sometimes be viewed as manipulative. Some tend to become a little power drunk and stop pulling their full weight. They can hide this by charming other people into doing more than their duties actually entail.

What Is a Team Worker?

Team workers are natural diplomats who act to reduce harmful friction between their teammates. They’re highly perceptive and can read team dynamics well. They often can spot people problems before their colleagues do. Team workers can tackle emerging problems proactively. They also make good negotiators during a conflict. Team workers keep a team running like a well-oiled machine.

One of the team worker’s primary strengths, remaining neutral and unbiased, can also be their weakness. The fact that they don’t typically pass judgment, even in seemingly clear-cut cases, can rankle with team members who think they’re clearly in the right.

Allowable Weaknesses: Team workers have a tendency toward indecisiveness in high-pressure situations and can seek to avoid conflict.

What Is a Resource Investigator?

The resource investigator is a true people’s person, a social butterfly who functions as the external face of the team. Energetic, charming, and extroverted, they excel at representing the team and delivering favorable outcomes when negotiating with stakeholders — something that doesn’t come easily to many.

Resource investigators dislike getting stuck in the nitty-gritty of team tasks, preferring social stimulation to detail orientation. They crave variety, meaning they’re not well suited to formal roles that call for long-term enthusiasm for a more repetitive task.

Allowable Weaknesses: Resource investigators can be vulnerable to over-optimism, and their initial enthusiasm can fade quickly.

What Is a Plant?

Plants are innovators, people who breathe creativity and novel ideas. They think out of the box, and they can see ways forward where other people cannot. Plants are most in their element on creative teams, where their unconventional thinking is appreciated.

Unfortunately, plants dislike rules and constraints, which means they often eschew norms and conventions and can tend towards unrealistic thinking. Many are sensitive, dislike confrontation, and can’t take criticism well.

Allowable Weaknesses: Plants can be less than meticulous with details and sometimes are forgetful. They can also get preoccupied with poor communication, which is a side effect.

What Is a Monitor Evaluator?

The monitor evaluator is a natural skeptic, a critical thinker who excels at applying logical principles and a wide pool of knowledge to decision making. Their keen analytical thinking skills mean they’re recognized for reliable, well-informed decision making, and they’re likely to have the ear of the team leader.

Monitor evaluators play a critical role in team decision making, but their prioritization of critical, analytical thought means they can come across as dispassionate and reactive. Plants, in particular, may feel that monitor-evaluators exist solely to tear their ideas down.

Allowable Weaknesses: Monitor evaluators can be too critical and fall short in their ability to inspire others.

What Is a Specialist?

The specialist is a knowledge-bearer, the trusted source for information in a specific field or area. They’re the team’s resident expert, and they focus on developing a particular set of skills, usually critical for meeting the team's goals. Specialists are conscious of their status as such in the group, and work hard to make sure that they maintain it.

However, specialists’ single-minded focus means they’re usually not very well-rounded, and as such, they’re not always able to see the bigger picture.

Allowable Weaknesses: Specialists can get bogged down in technicalities and focus their efforts too narrowly.

Three Categories for Belbin Team Roles

You can classify these nine team roles into three groups, based on which aspect of group work is their primary focus.

- Thought-oriented: Plants, monitor-evaluators, and specialists. They deal mainly with ideas and abstractions, and essentially determine the course of a project.

- Action-oriented: Shapers, implementers, and completer finishers. They’re concerned mainly with the actual performance of project work, and they’re responsible for ensuring that a team project achieves its tasks and goals.

- People-oriented: Coordinators, team workers, and resource investigators. They manage a team’s most valuable resources: its people. Without them, teams wouldn’t be able to work together or with external stakeholders.

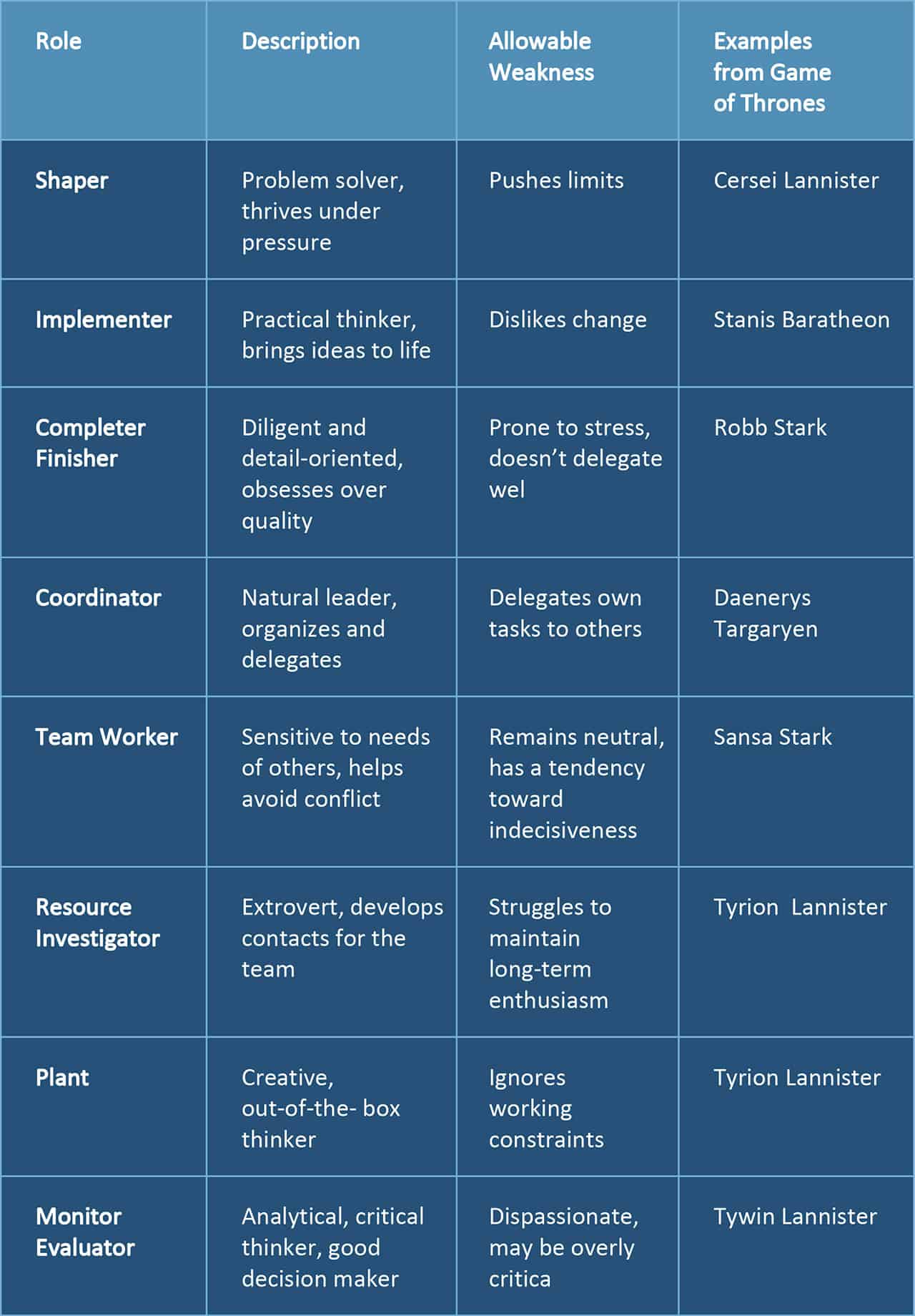

The chart below summarizes Belbin’s roles, their allowable weaknesses, and some famous fictional characters who embody each role type.

Britain’s Belbin Pioneers Team Role Theory

Implementers are practically-minded people who excel at taking ideas off the page and into the real world. They’re goal oriented, which means they’re good at creating plans that turn concepts into results. Efficient and well organized, implementers are highly disciplined, and they thrive in consistency.

Implementers' fondness for consistency means they typically dislike change, especially if they see it as change for change’s sake and not to meet a viable end. As such, some team members may consider them narrow-minded.

Allowable Weaknesses: Implementers can be inflexible and slow to adapt to changes.

How Belbin Team Roles Shine In Different Phases

At various stages of a project, the strengths of particular Belbin team roles become more important. Here are some examples:

Setting and Pursuing Goals: Setting goals based on team consensus is typically the coordinator’s responsibility. While coordinators are also generally responsible for ensuring progress toward goals, not all of them are suited to leadership under pressure. As these times, a shaper has the aptitude for propelling the team through obstacles, so they remain on track.

Creating and Finding Ideas: Ideas can come from both inside and outside a team. Within the team, the plants usually come up with ideas. Outside the team, resource investigators may hit on potential ideas during their many diverse interactions.

Building and Refining Plans: Once ideas emerge, they’re promptly deconstructed by monitor-evaluators. If they pass the evaluators’ criticisms, implementers shape the ideas into viable plans. Specialists provide expert opinions on whether plans are viable.

Organizing People: After making plans, the coordinator assigns tasks according to individual skillsets and puts people to work, making sure that everyone pulls their weight.

Following Through: Implementers ensure a plan is proceeding as intended and the team is on track to meet their goals. They have an ally in completer finishers, who check that the team’s output meets established benchmarks.

Maintaining Contacts: No team works in isolation, and it’s the resource investigator’s job to maintain relationships with outside stakeholders and resources. But contacts must also be kept smooth between team members, and team workers take charge of maintaining healthy working relationships.

It’s also possible to connect the Belbin roles to a widely understood model of project stages - Bruce Tuckman’s “Forming, Storming, Norming, Performing” framework. Tuckman’s model is based on the idea that a team convened to work on a project passes through four recognizable stages: Forming, Storming, Norming, and Performing.

During the forming stage, team members are sizing each other up. They make introductions and everything is civil, but they don’t fully trust each other yet. At this stage, the team’s focus is on getting to know each other and understanding their upcoming project. The coordinator’s and team worker’s roles are vital here because they help team members build working relationships and align the team toward their common purpose. Action-oriented team members may find it hard to steer clear of the fine details at this stage, but it’s too early to get bogged down in the task at hand. The team members must first develop working relationships and a mutual understanding.

Things get messy once the team is ready to immerse themselves in the work. This period is the storming stage, and it’s characterized by conflict between plants and monitor evaluators. Conflict helps stress test ideas and validate plans. It can also quickly spiral out of control, and still-young relationships can take lasting hits. The team worker and coordinator can help ensure that conflict remains productive, and the specialist oversees the application of knowledge in creating plans and ideas. Since storming can be a high-stress stage, shapers can defuse tensions by ensuring that energies are targeted toward addressing a shared problem, rather than at other team members.

Once the conflict has died down and the team gets going on project tasks, they enter the norming stage. A general consensus on plans has been established, responsibilities have been assigned, and the team has been organized into a working unit. Implementers make sure that the project is proceeding according to plan, while resource investigators deliver what the team needs to achieve its goals. And though the worst of the conflict should have passed, team workers can help their teammates learn to work together in ways that create more synergy.

By the time the performing stage rolls around, the team should be running at close to optimum efficiency and synergy. Completer finishers take on responsibility for the team’s end product, stressing over whether things have been done according to plan. The shapers work alongside them to push the team over the line, and use a goal that should now be in clear sight to motivate the team and to help it power through obstacles.

Determining Your Team Role: What Is the Belbin Test?

As you read the description of the team roles, maybe you immediately knew which one you are. Or maybe you spotted your team mates in other roles. However, most individuals do not conform exactly to one Belbin role. Most people play at least two or three roles well and could fill a few others if needed.

For that reason, you do not need to have exactly nine people on every team to make sure to cover all roles. Some roles are more likely to co-occur in individuals. (People who are both shapers and coordinators, for example, are less rare than individuals who are both plants and monitor evaluators.) This is because stronger dissimilarities exist between certain roles than between others. While this means that archetypal conflict is unlikely, you’ll also occasionally run into combinations of people with inherently good or bad chemistry because they each play multiple roles that are either complementary or conflicting.

So how do you know for sure which role you are?

Belbin Associates offers a number of variations of the Belbin Team Roles assessment. The basic version is a self-assessment that you can supplement with assessments by people who know you. The individual assessments form the basis for a team assessment, which examines how individuals would work together in a hypothetical team and how two specific individuals might work together. Belbin Associates also offers an assessment of the Belbin roles required for a specific job position to help decide whether an individual is a good match.

The company, which was founded by Belbin, owns sole rights to administer assessments based on Belbin’s nine roles. There are some team role assessments available free online such as this one. Some of these free versions borrow heavily from Belbin's nine-roles model, so there are questions of proper use.

An official Belbin assessment starts at about $55 for a single individual report, with discounts of over 50 percent available for reports purchased in bulk. Team reports start at about $120. You don’t need to be accredited to interpret a Belbin report, but if you work in training or human resources and frequently use the Belbin roles, you might consider getting accredited by Belbin Associates.

In the past, it was common practice to use a self-scoring version of the Belbin Self-Perception Inventory included in Belbin’s 1981 book. Belbin Associates says this assessment is now out of date since it includes only the eight original Belbin roles and lacks the balance of observer assessment.

Belbin added observer assessments to the process because he recognized that there may be significant differences between how people see themselves and how their colleagues perceive their behavior. The observer assessments supplement the self-assessment for a more well-rounded profile than the individual assessment. You can use the observer assessments for 360-degree feedback.

If you’re interested in seeing what you can get from a Belbin assessment, Belbin Associates provides a sample individual report. The report shows how an individual’s behavior aligns with behaviors typified by each of the nine roles, identifying your roles by order of preference. It also compares the results of self- and observer assessments and provides a detailed discussion of one’s strengths and weaknesses, complete with advice on how to develop. The report ends with a rundown of suggested "work styles,” which are general principles of behavior that draw on individual strengths.

Belbin also provides a sample team report that identifies strengths and shortcomings within a team, as well as who plays each of the roles well and how much the team relies on them to play said roles.

Understanding and Maximizing Your Team Roles

Whatever the results of your team role assessment, it’s important to remember that team roles are not static. Your role can change with time, from project to project, and even as the project transitions through phases. All behaviors, while to some degree rooted in personality, can change.

These roles are a combination of innate tendencies and learned skills that one can refine with practice, such as improving analytical thinking skills. For example, when a project moves to a different stage in its lifecycle, the emphasis shifts: a project transitioning from storming to norming also shifts emphasis from thought to action. Team members will likely be engaging in different behaviors even if they’re not conscious of it. Belbin consultants suggest that team roles can shift as people gain experience, go through life and career changes, and actively target behaviors for improvement.

Remember, there are no “good” or “bad” team roles. Each role has strengths and weaknesses, and each role is necessary to ensure team success.

Focus on improving the strengths you already have, since those will enable you to have the greatest impact. In addition, remain conscious of your weaknesses, and remember that nobody is good at everything.

Belbin has good advice for each team role on what to do and not do. For example, specialists are encouraged to show enthusiasm for their subject, encourage others to trust their knowledge, and keep their expertise up to date. They are urged to avoid discounting the importance of factors outside their domain and becoming protective of their turf.

All team members should be encouraged to be open about their preferred roles. By sharing your strengths and weaknesses, you increase role clarity, improve communication and synergy, and help everyone manage their expectations.

Knowing everyone’s roles also helps the team to spot structural deficiencies. Too many shared strengths may cause team members to channel their energies toward competition rather than results; too many shared weaknesses may mean the team has a handicap or blind spot. Roles in balance make for a well-rounded team.

One version of the Belbin Team Roles assessment allows you to assess the fit between two individuals — such as a manager and their report, or two peers — to see how their roles match.

Team Role Sacrifice and How Roles Relate to Freelancers

At other times, team members may need to forego their preferred role to best meet the team’s needs. Belbin calls this a team role sacrifice, meaning you put the team’s needs before your own preferences.

A team role sacrifice is not necessarily a negative thing. In fact, it can be an opportunity to develop helpful behaviors associated with your secondary or tertiary roles. But remember: team role sacrifices should not be the norm. If you find yourself adopting weaker roles so often that you’re not able to engage in your strongest roles, this is likely a symptom of an imbalanced team.

Team role theory also has relevance for freelancers. Managers may need to recruit a freelancer to fill a specific role on a project, and knowing candidates’ team role type can help get a good fit. Freelancers who know their role strengths are better able to articulate their potential contributions to clients and project teammates. Understanding how different roles interact within teams can make it easier to slide into an existing team or take on a temporary assignment.

Evidence to Support Team Role Theory in Practice

Researchers have debated the validity and reliability of the Belbin team roles theory since the 1990s, especially over the original concept of eight roles and the self-scored self-assessment. The newer iterations of the Belbin assessments, which have standardized scoring and incorporate 360-degree feedback, boast higher reliability and validity, according to studies by European researchers.

Some studies have shown that the use of Belbin’s theory of team balance is associated with improved performance in educational settings, but there appears to be substantial variation indicating where, when, and how performance improves.

For example, one study of Dutch university students showed that group role balance was positively associated with performance improvements only during the preliminary phases of a group project. Balanced roles were positively related to a group’s cognitive complexity but negatively related to teamwork quality. Another study by university students in Finland suggested that building teams according to Belbin theory increased both student satisfaction and, perhaps consequently, student performance.

Activities to Help Teams Understand Their Team Roles

Any discussion of Belbin team roles can be made engaging, or even gamified. Belbin provides supporting resources for a number of team-roles-based activities that are designed to increase understanding of team roles and their practical ramifications on teamwork. You can find more great team-building activities and exercises here and here.

The Belbin Team Role Circle: Team Role Circle is a quick exercise that involves a pie chart with all nine Belbin roles as slices of the pie. Each team member adds their name to two slices of the pie representing their two most-preferred roles. When everyone has done this, it’s easy to see the distribution of various roles within the team, and team members are encouraged to discuss structural strengths and weaknesses based on their makeup.

The Crisis Exercise: The crisis exercise, developed by psychologist and trainer Rob Green, is simple in theory, but takes a couple of hours to run. To start, split participants into a number of teams according to their Belbin roles. You could have as many as nine teams, but depending on the size of the group and the time you have, you may want to collapse some team roles into larger groups based on whether they’re action-, thought-, or people-oriented.

The crisis exercise has two main parts. The first is an hour-long consultation in which each team devises a “crisis” of any kind and proposes a solution to their crisis that has the full buy-in of all team members.

In the second part, they present their crisis and solution to the other teams. This provides insight into how people playing different team roles think and solve problems, due to a phenomenon Green calls "team role resonance,” which is the exaggeration of common strengths and weaknesses in a group. Without dissimilar team roles in the groups, each crisis and solution tend to reflect heavily the role types that created them.

Belbin Contribute: Contribute is a team comprising of nine tasks, each of which is associated with a single team role. The team decides which member will perform each task, from writing captions to sourcing a purple shoe, to guiding other members of the team into a sheep pen. The aim is to collect team role awards associated with the nine tasks within a fixed time period.

Like the team role circle, Belbin Contribute is designed to show why a team needs representation of all nine team roles to achieve balance and to tackle different types of challenges.

Belbin Co-operate: Another product from Belbin, Co-operate is based on three action-oriented exercises that call for participants to use communicative, cooperative, and decision-making skills. The exercises include solving a set of puzzles co-operatively, rescuing a “rocket,” and controlling a writing apparatus as a team to create recognizable drawings.

Team Role Alignment Exercise: This exercise, available from Belbin, is a simple game that involves classifying behaviors as either “helpful things to do” or “things to avoid” for each of the nine team roles. It’s meant to build understanding of how to interact with people with different preferred team roles than your own.

Project Stages: In this simple exercise, a team breaks down a project into a series of distinct stages, then identifies the team-role-based behaviors that are critical for success in each stage. It can be done both for a hypothetical project and as an exercise before starting a real project.

Alternative Role Classification Systems

Belbin’s theory may be the most commonly used model for team roles, but it’s not the only one.

Many of the other role classification systems used today are based on dimensions other than behavior, but they all revolve around the idea that teamwork is effective when it capitalizes on individual differences. These differences aren’t inherently good or bad. If identified and harnessed, they benefit the team by creating a unit that’s stronger than any individual. If unrecognized and unappreciated, however, they become a source of friction and even conflict.

The Margerison-McCann Team Management Profile

Team Management Systems offers the Team Management Profile Questionnaire, a 60-item assessment that measures individuals’ "work preferences” on the Margerison-McCann Team Management Profile.

The profile can be thought of as a psychometric test and uses the assumption that people enjoy some types of work more than others and that they’re motivated to perform better on these “preferred” types of work. By matching people’s actual responsibilities to their performance strengths, you improve performance while increasing team member’s levels of motivation and personal satisfaction.

The Margerison-McCann Profile has eight primary classifications:.

- Reporter-Adviser: Gatherer of information, willing to provide support to team members

- Creator-Innovator: Creative, imaginative, likes complex ideas and thinks about the future

- Explorer-Promoter: Extroverted, a charmer who persuades others and likes socializing

- Assessor-Developer: Analytical, likes experimenting and putting ideas into practice

- Thruster-Organizer: Goal oriented, pushes towards objectives in an organized fashion

- Concluder-Producer: Likes setting up reproducible, efficient processes that deliver

- Controller-Inspector: Diligent and detail oriented, takes pains to meet standards

- Upholder-Maintainer: Guided by values and morals, driven by their sense of purpose

The Star Roles Model

The Star Roles model describes relationships between mentors and mentees as falling into one of two primary categories: Inner roles, which correlate with introversion and focus on “closed” mentoring of the individual in a kind of self-exploration; and Outer roles, which correlate with extraversion and focus on helping the mentee navigate the work environment effectively. Each of the two primary role categories is further split into three roles.

The three Inner roles are:

- Greater Expert: Mentor shares own knowledge and experience with mentee

- Critical Partner: Mentor uses the Socratic method to stimulate and challenge mentee

- Sympathetic Ear: Mentor serves as a trusted confidant and sounding board for mentee

The three Outer roles are:

- Background Champion: Mentor raises external support for mentee, supports cause

- Role Model: Mentor uses own past experience to guide mentee through challenges

- Cultural Navigator: Mentor imparts in-depth understanding of how organization works

The six roles are not mutually exclusive pathways, but rather preferences for different approaches, and they can be used to review mentor-mentee relationships and to find whether the mentor’s methods are actually serving the mentee.

Robert Heller’s Seven Roles

Business journalist Robert Heller, who wrote the 1999 book Essential Manager: Managing Teams, identified seven team roles that relate to specific functions within teams rather than behavioral preferences. Heller’s self-explanatory seven roles are Leader, Critic, Implementer, Diplomat, Coordinator, Innovator, and Inspector.

In contrast to the Belbin roles, Heller’s roles relate to specific functions within teams rather than tendencies to behave in certain ways. While individuals with specific personality strengths could conceivably adopt Heller’s roles, they’re more loosely defined than the Belbin roles. Additionally, the emphasis here is less on people taking on roles that fit, and more on people taking on the roles the team needs to operate effectively.

There are a number of other role classification systems that use a functional view of team roles. These are appealing to many managers since functions can be directly connected to hard skills. One commonly used system is the five-role Leader, Recorder, Analyst, Expert, Facilitator team, which is based on the idea that five people is the perfect size for a team.

Edward de Bono’s Six Thinking Hats

In 1999, physician and psychologist Edward de Bono wrote a book called Six Thinking Hats, which would become world famous for its easily understandable visual metaphor of six colored hats to identify six distinct thinking styles: objective, opportunistic, cautious, passionate, fertile, and abstract. While people tend to be stronger or more practiced at some thinking styles than others, de Bono’s point was that people are not constrained to only a few thinking styles. He used easily changed hats to illustrate how a single person might approach a problem in a number of different ways.

De Bono termed this parallel thinking, a phrase that has caught on for people solving complex problems, whether as individuals or in groups. The idea is that considering a number of perspectives when making a decision results in a more holistic, well-thought-out decision.

Adam Grant’s Givers and Takers

Adam Grant, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, identifies three types of workers: takers who seek to get as much as possible from others, givers who seek to help others without expecting anything in return, and matchers who are willing to help those who help them.

Grant analyzed lots of organizations and teams for his book Give and Take. While all three types offer something to their teams, teams with more givers were across the board stronger and more effective. That’s surprising when weighed against his finding that givers as individuals were overrepresented at the top as well as the bottom on success metrics.

Identifying true givers is difficult because, contrary to expectations, they aren’t necessarily the most likeable. "Disagreeable givers are the most undervalued people in our organizations, because they're the ones who give the critical feedback that no one wants to hear but everyone needs to hear," Grant says.

Other research by Grant suggests that the shared experience of a team working together is a stronger predictor of success than the experience of individual members. Harvard University Professor Richard Hackman, an authority on team effectiveness, says that shared team experience is crucial to team performance, which suggests that keeping team composition stable is important.

In addition to Grant’s findings on disagreeable givers, scholarly research on how prior friendships affect the outcome of a group’s efforts has reached different conclusions, as researchers from the Stanford Center for Innovations in Learning observed in this 2009 paper.

For example, one oft-cited study has shown that “friendship collaborations” feature more intense social activity, more frequent conflict resolution, more effective task performance, and high levels of mutual liking, closeness, and loyalty. Yet the same study also indicated that groups of friends disagree more frequently and are more concerned with resolving disagreement, and other research acknowledges that “dense social network ties” among group members can discourage productive conflict and debate, which will likely lead to non-optimal performance.

But there’s another, more fundamental downside to letting groups self select, and it has to do with the personality characteristics of groups of friends. According to a 2017 study, objective measurements of people’s personalities show that friends are substantially more similar than strangers. As one of the study’s authors, David Stillwell of the University of Cambridge, put it, “People … befriend others who are like themselves, and birds of a feather do flock together after all.”

This means that people who self select teammates from among their friends tend to form groups that are relatively homogenous, personality-wise. That poses a problem for teams that need synergy to thrive.

Gauging Team Roles on Behavior Spectrums

There are a number of other ways to classify team behavior, but unlike the role systems we’ve discussed, these are framed as spectrums. Having people who fall all across the spectrum can help balance a team.

Doers and Thinkers: Some people prefer planning courses of action and figuring out ways to meet goals, while others like getting their hands dirty to put plans into action. Both types of people are vital in teamwork. It’s important to know what you want to do and how you want to do it, and it’s just as important to actually get it done.

Divergent and Convergent Thinkers: Divergent thinkers excel at crafting a wide range of ideas to get things started. Convergent thinkers are good at winnowing these ideas to the most feasible ones. Of course, neither group is able to function well without the other.

Self-Centered and Group-Centered People: By default, people tend to be self-centered, but it’s vital to be able to prioritize the needs of the team sometimes. If they don’t, they run the risk of polarizing the team and creating individual conflicts. On the other hand, people who tend too far toward group harmony may not adequately represent their own views out of a desire to avoid conflict.

Intuition and Facts: It’s extremely difficult for a fact-based thinker to accept intuition as a worthy basis for decisions and for an intuitive thinker to dismiss what their gut is telling them. Generally, teams tend to give more weight to facts, though experienced individuals might be given a pass when they invoke intuition, since there’s a general appreciation for learned experience in almost all industries.

Styles of Leadership Influence the Success of Team Leaders

Of all a team’s members, the leader is most often the focus of attention. The leader tends to be the most visible figure within the group: their leadership (or lack thereof) can make or break the team’s efforts, and they’re usually the one ultimately held accountable for the team’s work.

It is perhaps for these reasons that research into leadership predates research into team roles in general. One classic study was conducted in 1939 by psychologists Kurt Lewin, Ronald Lippitt, and Ralph White at the Child Welfare Research Station at the State University of Iowa. The psychologists identified three styles of leadership decision making: autocratic, democratic, and laissez-faire. Autocratic leaders make decisions without consulting the team, then enforce them and expect obedience; democratic leaders involve the team in decision making while accepting accountability for meeting the stated objectives; and laissez-faire leaders adopt a hands-off approach.

It’s important to note that despite the negative connotations of the terms “autocratic” and even “laissez-faire,” each style may be appropriate for specific situations, even within the same team. For example, autocratic leadership may be the norm for military teams in the field, while laissez-faire leadership is preferred where individual freedom is prioritized, such as when “leading” a team of self-directed, inherently productive individuals — academics being the classic example.

In the mid-1960s, psychologist Fred Fiedler, who studied leaders, claimed that no single style of leadership was inherently superior, but that the effectiveness of leadership depended on the style of leadership adopted in a particular situation. His Fiedler Contingency model contends that effectiveness results from two factors: leadership style and situational favorableness.

Fiedler categorized leadership styles as tending toward either task orientation or relationship orientation. Task-oriented leaders are primarily interested in pursuing concrete objectives and meeting goals. For them, the end is more important than the means. Relationship-oriented leaders are primarily interested in personal connections, so they are better at managing people. They care about the manner in which a team meets its ends. (Relationship orientation is related to a concept called maintenance orientation, which describes the practice of maintaining working relationships within a team by setting standards for conduct, creating and fostering good relationships, and arbitrating when necessary.)

Situational favorableness is a function of three distinct factors: the levels of trust and confidence between leader and team (leader-member relations); the nature of the task the team will perform (whether it’s structured or unstructured, or task structure); and the leader’s power to control the group ( leader's position power). Any combination of these three factors is possible, making for eight possible situations. There is a recommended leadership type — task oriented or relationship oriented — for each situation.

Team Roles in Projects Including Software Development

For a team that’s set up to undertake a specific project, people are usually selected on the basis of hard skillsets, rather than behavioral tendencies or thinking styles.

We can divide these skillsets into four main categories:

- Technical skills or professional knowledge to perform specific functions

- Problem-solving skills, which are more broadly applicable

- Teamwork or interpersonal skills, which are necessary to work together effectively

- Organizational skills to perform the complex task of running a team effectively

These all come together to advance the team toward its goal.

Let’s look at some of the formal roles in and around a team working on a software development project.

- Project Manager: The project manager sets the scope of the project and picks the project team. He or she also allocates the project budget, communicates project expectations to the project team, and liaises between the project team and external stakeholders. Project managers typically tend toward thought- and people-oriented roles.

- Project Sponsor (or Executive Sponsor): The project sponsor accepts high-level accountability for a project and champions its cause at the higher levels of the organization. They too tend towards thought- and people-oriented roles in their function as project sponsor.

- Technology Support: The technology support staff are people- and action-oriented individuals, usually not part of the core team, who ensure that the team operates smoothly and efficiently.

- Business Analyst: The business analyst is not part of the project team, but fulfills a number of associated functions. For example, he or she may work with the project manager to set the goals and objectives for a project. Business analysts are typically thought- and action-oriented.

- Key User: The key user is a person who holds majority knowledge about a certain system, a process, or procedure. Key users are integral members of project teams and aren’t restricted to particular roles.

- UX Designer: The UX designer is responsible for how a software product is designed to “feel” for its end users. They’re largely people- and thought-oriented individuals who work closely to shape how customers perceive the final product.

- Usability: Usability describes quantifiable measures of how easy a product is to learn and use, making it a more precise science than UX. Usability specialists tend to be people- and thought-oriented, but also rely on action-oriented behaviors.

- Subject Matter Expert: Subject matter experts are most similar to Belbin’s specialists. They’re thought-oriented individuals who provide specific know-how for software development projects, ranging from content creation to design.

- Application Developer: Application developers are action-focused individuals who create and engineer software. Their work is the culmination of the project team’s creative efforts.

Some software development methodologies, such as Scrum, call for specific roles that execute the methodology. In Scrum, these include the product owner and the Scrum Master:

The product owner is in charge of identifying requirements for the project, then prioritizing the development team’s deliverables to meet these requirements.

The Scrum Master is a kind of team leader with extensive experience in Scrum methodologies. As members of the project team, they’re closely familiar with the project’s requirements, with the developers, and with the overall state of the project. It’s the Scrum Master’s responsibility to ensure that the sprints (time-based periods of effort) run smoothly. Often, this involves liaising with the project owner over what the deliverables are for each sprint, so that the software developers don’t have more work than they can handle.

Some studies suggest that team balance as defined by Belbin’s theory is positively associated with team performance, which means team builders should take balancing people into account when creating teams.

With any project team, the person accountable — typically the team leader, but often also the project manager and the project sponsor — has to keep an eye open for free riders, who reap the benefits of team membership without pulling their weight. Social psychologists call this social loafing, when people exert less effort to achieve a goal when they work in a group than when they work alone (the opposite effect is called social laboring). French agricultural engineer Maximilien Ringelmann did experiments with groups pulling on a rope to show that members of a group become less productive as the size of the group increases, which is known as the Ringelmann effect.

Social psychologists Steven Karau and Kipling Williams did an influential meta-analysis on social loafing in 1993 and found several variables that could counteract the free rider problem. These included the meaningfulness of the tasks and culture. Wharton Professor Adam Grant, mentioned earlier, expanded on that work to identify ways to spur team members to produce their fair share. His strategies include making inputs visible, shrinking the size of the team, demonstrating what other teammates are accomplishing and assigning unique responsibilities.

Similarly, it’s also important to clarify the benefits of team membership. Financial incentives might be the safest bet, but it’s also possible to offer team training or professional experience as a benefit for teamwork.

The project team leader’s role is vital. Harvard Business Review identifies six roles that a project team leader must play. These include the initiator, who prompts the team to follow their plan of action; the model, who sets an example for the team; the negotiator, who represents the team externally; the listener, who watches for signs of trouble within the team; the coach, who helps their teammates develop; and the working member, for the leader is also a part of the team and must take on their share of work.

Ultimately, while you’ll often select a team on the basis of hard skill sets, you should keep behavior and personality traits in mind in order to create a team groomed for success.

Track Team Goals in Smartsheet

Empower your people to go above and beyond with a flexible platform designed to match the needs of your team — and adapt as those needs change.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.