What Is the Sarbane-Oxley Act?

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act is a U.S. law that encourages transparency in financial reporting and corporate governance in public companies with the intention to protect investors and the public against corporate financial fraud and mismanagement. The law, also known as SOX or Sarbox, closes loopholes in accounting practices that in the past permitted misstatements of company value. The law also holds corporate management accountable; this includes CEOs, CFOs, boards of directors, and the public accounting firms that may work with and conduct audits for public companies.

To ensure higher standards of governance, companies must establish and comply with internal controls on financial reporting. These controls are intended to protect the integrity of the data that builds financial records and the integrity of the annual report. As information security consultant Terumi Laskowsky says, “Integrity means people are not able to tamper with the data and that it is accurate.”

In addition to providing an assessment of the financial statements, external auditors also must provide an opinion on the adequacy of the company’s internal control structure. In addition, both CEOs and CFOs must certify the accuracy of the company’s financial statements and annual reports. CEOs and CFOs who sign misleading or fraudulent reports can be prosecuted; if found guilty, penalties include up to 20 years in prison and fines of up to five million dollars.

Although the main goal of the 11 parts (or titles) of Sarbanes-Oxley is to increase transparency in accounting and reporting, many provisions also influence information security, data storage and exchange, and electronic communication.

The key points of Sarbanes-Oxley are as follows, with the section number noted:

- To ensure and prove the accuracy and timeliness of financial data, a company must impose controls and validation on any financial systems it uses to prepare financial statements. (Section 404)

- The Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) is established as a non-profit organization to draft auditing guidelines, train auditors to generate accurate, independent reports, and supervise auditors and auditing firms. (Section 101)

- Public accounting firms who provide auditing services are prevented from providing bookkeeping or stock valuation services for the same company without pre-approval from the PCAOB. (Section 201)

- Auditors must report all critical accounting policies and practices to a company's audit committee. (Section 301)

- Auditors must rotate off a project every five years and avoid work on that project for another five years. (Section 203)

- CEOs and CFOs must certify that financial statements accurately and fairly represent the financial condition and operations of the company. If they fail at this task, they can face possible financial penalties or prison. (Section 302)

- Companies may not make loans to their executives or to members of their boards of directors. (Section 402)

- Public companies must implement an internal control system for tracking and auditing financial processes. (Section 302)

- The external auditor must report on management's assertions about a company’s financial system. (Section 404)

- Companies must disclose any substantial changes in their financial conditions in a timely manner. (Section 409)

- It is a crime to destroy, change, or hide documents to prevent their use in official legal processes. (Section 802)

- Companies must keep audit-related records for a minimum of five years. (Section 804)

- The U.S. Department of Labor protects employees, so called whistleblowers, who provide evidence of fraud. Sarbanes-Oxley prescribes penalties of prison and fines for retaliation against whistleblowing employees. (Sections 806 and 11107)

History of Sarbanes-Oxley

Multiple instances of questionable financial practices in large U.S. companies and accounting firms in the late 1990s and early 2000s precipitated the creation of Sarbanes-Oxley. In companies such as WorldCom, Tyco, and Peregrine Industries, misleading financial reports resulted in artificially-inflated stock values.

Revelations of corporate financial misconduct culminated with the bankruptcy of Enron. As one of the top-ten largest corporations in the U.S. at the time, Enron managed a diversified portfolio of oil and gas development, energy sales, and telecommunications. However, undisclosed partnerships hid failing aspects of the company — this allowed earnings to be overstated, which generated increased stock prices.

Enron employee pension funds and individual 401Ks were heavily invested in Enron stock. When the company failed, millions of investors found their stock portfolios devalued and depleted. In the case of Enron, reallocations to other stock choices were unavailable during the time when the stock was losing market value. Many individuals lost as much as ninety-four percent of the value of their retirement plan. By contrast, some C-suite employees had significant financial gains in preceding years by exercising stock options that were valued at less than the current price.

The financial controversies also raised questions about practices in large accounting firms, such as Arthur Andersen. Among other activities, some Arthur Andersen employees were accused of destroying paper and electronic documents while the SEC conducted a review of Enron.

With the 2001 bankruptcy of Enron, Senator Paul Sarbanes and Congressman Michael Oxley drafted new legislation to strengthen existing SEC legislation and to create new laws. The full formal name is Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002, and was known in the Senate as the Public Company Accounting Reform and Investor Protection Act, and in the House of Representatives as the Corporate and Auditing Accountability, Responsibility, and Transparency Act. SOX aimed to provide greater oversight over public accounting firms, increase executive accountability for the content and accuracy of company financial reports, and escalate penalties for not adhering to the new legislation.

When signed into law, President George W. Bush called it "The most far-reaching reforms of American business practices since the time of Franklin D. Roosevelt. The era of low standards and false profits is over; no boardroom in America is above or beyond the law."

The Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) administers Sarbanes-Oxley. Established in the wake of the stock crash of 1929, the formation of the SEC followed the 1933 Securities Act, which required that brokers provide, at a minimum, a detailed stock prospectus to potential investors. The creation of the commission in 1934 is considered the most important U.S. financial security legislation of the 20th century.

Benefits and Pitfalls of SOX Compliance

While some commentators see SOX legislation as forward-looking and anticipatory of later financial problems in 2008-2011, others see it as precipitating the Great Recession by adding unattractive costs to doing business in the U.S. compared with other countries.

Originally, some thought that SOX would limit capitalization for new IPOs and stifle innovators, but other opinions point to evidence that the law increases investor and fund manager confidence, and that the pricing of IPOs is therefore more accurate. In addition, SEC Rule 144a now allows trading entities (stock exchanges) to trade among themselves securities considered risky for the general public. In this way, companies can avoid SEC registration and the requirements of SOX, yet still find capital.

The true costs of Sarbanes-Oxley to business may also be difficult to quantify. Smaller companies (fewer than 100 people) may be more susceptible to fraud because smaller teams can mean fewer segregations of duties. Compliance to section 404, in which the auditor attests to the effectiveness of internal controls, can be costly. However, these smaller companies were never required to complete the auditor’s report on internal controls. In addition, Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 permanently exempts companies with under $75 million in public float, or offered shares, from the auditor report.

Adhering to SOX does add expenses for legal advice, an external auditor, and directors and officers (D&O) insurance, as well as lost productivity while preparing for the many audits. Some suggest that although entities pay considerable initial setup costs, once implemented, SOX becomes more efficient and thereby less expensive to maintain. Nevertheless, a popular 2008 SEC survey showed that costs to administer SOX average $2.3 million, more than the projected annual costs of $91,000.

Sarbox was supposed to force executives to return any bonuses awarded within a year of malfeasance. However, it seems that in most cases, companies have established policies requiring individuals to return benefits before the SEC sanctions them. However, in over 10 years since enactment, Sarbanes-Oxley has been directly responsible for few corporate fraud prosecutions. Instead, SOX has effectively forced companies to layer certification. Rather than CEOs following the day-to-day work of middle-level employees, managers now certify controls and reports and pass those certifications up to the C-suite.

What Are the Requirements of SOX?

Although the Sarbanes-Oxley Act consists of 66 pages containing 11 titles or sections, companies are only subject to a few essential requirements.

Section 302: CEOs and CFOs are responsible for accuracy and veracity of financial reports, and have noted any deficiencies in internal controls or instances of fraud.

Section 401: Firms must release financial reports with full disclosure of entire material condition of the company, including off balance sheet liabilities and transactions.

Section 403: Principal stockholders and management must disclose any company-related transactions.

Section 404: The CFO and CEO must personally certify that they stand behind financial reports. Firms must establish internal financial controls and corporate officers must sign off that they have verified the effectiveness of the controls within 90 days of publishing the annual report.

Section 409: If a firm experiences any material changes in their financial or operating conditions, they must inform shareholders immediately, or as the act says, “on a rapid and current basis.”

Section 802: Companies can not destroy, alter, or conceal records, documents, and objects relating to finance and business transactions - in particular, if these actions could obstruct a legal investigation. These documents must be kept for a minimum of five years. Noncompliance could lead to prison.

IT Security Implications

Although the act does not mention computer networks and devices, IT plays an important part in SOX compliance because electronic communications and storage are integral to modern business practices.

Penalties for Noncompliance

Prescribed penalties for noncompliance with SOX regulations are severe. They include the following:

- Delisting of stock from public stock exchanges

- Fines of up to five million dollars

- Invalidation of D&O insurance policies

- Up to 20 years in prison (for CEOs and CFOs who willfully submit an incorrect certification audit)

- Clawback of any bonuses paid within a year of any malfeasance

Does the SOX Act Apply to You?

Sarbanes-Oxley applies to all publicly held U.S. companies. International companies are also subject to the act if they have registered equity or debt securities with the SEC. SOX also applies to any accounting firm or third-party service company that provides financial or finance-related services to applicable companies. Service organizations include data centers, Internet Service Providers (ISPs), and so on.

What Is Subject to SOX Compliance?

All company financial and business transaction records and data, including electronic records and messages, are subject to audit. Networks and devices used to transmit and store pertinent documents must also be compliant.

Employee Tools and Devices

Employees often create their own tools to expedite work and aid usability, such as spreadsheets or SharePoint sites. If this shadow IT network contains or concerns financial information, anything included on it also must comply under SOX. “We have to make sure that the end user apps are also protected from tampering, and that the data going into the app as well as coming out of the app is accurate,” says Laskowsky.

Although companies usually support a bring your own device (BYOD) policy, just as for network security, it can present problems. Terumi Laskowsky is an internationally-recognized information security consultant and founder of Pathfinder Japan.

How Sarbox Affects Private Companies

Private companies may not have the same financial reporting requirements under Sarbanes-Oxley as public companies. However, private companies may consider implementing some aspects of the legislation such as the call for internal controls on financial data management. Another noteworthy practice is performing an annual audit on accounting and financial data and activities. The law does not compel privately-held companies to comply. However, customers may view SOX compliance as a key differentiator. If private companies work with or intend to work with public companies, compliance may be essential.

More substantially, non-adherence to some aspects of SOX can lead to prison, even in private companies. For example, it is illegal to destroy or change any records or documents to keep them from being a part of a criminal investigation, or in a federal bankruptcy proceeding. Penalties include fines and up to 20 years in prison.

Perhaps the most important consideration for private companies to stem from SOX is whistleblowers protection provisions. Retaliation against a whistleblower is illegal for all companies, and public companies must document procedures for dealing with complaints, in particular for complaints under federal jurisdiction, such as Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). In response, some private companies have drafted extensive guidelines for processing employee concerns.

Private companies adopt SOX-related guidelines to guarantee capital, reduce liability costs, and ensure public good will. If a company anticipates that a public company will acquire them, adopting these regulations can be important. Investors and lending agencies may be inclined to support a company when they perceive strong governance practices.

How Sarbox Affects Accounting Firms

Under Sarbox, accounting firms that provide independent auditors to a company may not perform other functions for that company. The types of activities restricted from external auditors include the following:

- Bookkeeping

- Auditing

- Business valuations

- Investment advice

- Banking

- Consulting

- Management

- Design and implementation of record keeping systems

How Sarbox Affects HR

Considering that HR and payroll manage records containing employee information, salaries, benefits, incentives, paid time off, training costs, and paychecks, it’s not surprising that SOX can influence how HR and payroll function. In particular, section 404 governs HR and payroll practices by requiring that companies assess and report on their own internal controls and provide an auditor’s attestation.

Frameworks for Establishing IT Compliance

Although Sarbanes-Oxley establishes the requirement for governance, it is not prescriptive and doesn’t state anything specifically about IT governance. For guidance CEOs and especially CIOs turn to other frameworks. Three main frameworks include:

- Committee of Sponsoring Organizations (COSO): This committee combines representatives from the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA), the American Accounting Association (AAA), the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), the Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) and Financial Executives International (FEI). Dating 10 years prior to SOX, the COSO framework specifies guidelines for internal control over financial reporting (ICFR). This accounting framework is highly regarded by the PCAOB and SEC.

- The Information Technology Governance Institute (ITGI) is a child creation of ISACA that researches issues of IT in business context to promote a better understanding among IT professionals of their role in enterprises.

- Control Objectives for Information and Related Technology (COBIT): Created by the Information Systems Audit and Control Association, now known by its acronym, ISACA, it provides a framework for management and governance of enterprise information technology. Its specifications are used for demonstrating compliance with data and IT components of Sarbanes-Oxley. COBIT contains 34 processes, of which 12 apply directly to SOX concerns.

- Statement on Standards for Attestation Engagements (SSAE-18): Reporting on Controls at a Service Organization provides a framework for allowing companies known as service organizations to communicate their cyber security effectiveness to certified public accountant auditors and others.

What Is SOX Compliance Testing?

SOX calls for regular testing of internal controls in organizations to provide evidence that they function correctly. Internal compliance teams usually conduct three rounds of testing in the course of a calendar year: initial control, interim test, and year-end test, which includes unique annual tests. Gathering and storing documents, samples, and evidence in a variety of formats may prove to be cumbersome and challenging. For larger organizations, automated testing and platforms that regularly gather audit information may be the solution.

Internal Controls

Internal controls are built around fraud risk analysis. For example, inaccurate payroll calculations is a risk. Calculations may be inaccurate among hourly wage earners because of buddy punching, wherein one employee punches the timeclock, or logs in for another employee who isn’t present. A control for this may include a camera near the access keycard. A test would include reviewing the camera footage and recording the results in a log.

Another risk might be payments to a bogus vendor. To prevent someone from creating a fake vendor to pay themselves, controls would include segregating the jobs of vendor creation and vendor payment between different people. To ensure that vendors are legitimate, one test is to scan the list of vendors for similar names and to verify that vendor addresses exist.

What Is a SOX Audit?

The SOX compliance audit happens once a year. A SOX audit must be separate from internal audits, although companies often schedule the compliance audit before the release of annual reports to meet the shareholder reporting requirement of SOX.

A PCAOB-approved external auditor conducts the audit. In addition to reviewing financial statements, records, and current and statements from previous years, the auditor often interviews staff to confirm their competency to perform their duties, verify the segregation of duties where required, and examine business processes. The auditor also confirms adherence to tax laws, and reviews assets and the accuracy of the company valuation.

A firm under audit must also reveal to the auditor any security breaches and how the firm remedied any conditions that precipitated the breach. During the audit, a firm must present a valid and current SSAE-16 or 18 for each partner service organization. An SSAE shows proof of the internal controls for each service organization the firm uses.

In addition to finding and hiring the auditor, the company being audited arranges all preparatory meetings. A first meeting with a chosen auditor involves discussions with management about expectations for the audit report.

Audit Trails and Evidence

An audit trail is a vital tool for proving that internal controls are effective and that the system is free of data breaches and fraudulent activities. You can manually create an audit trail with a log book or sign-in sheet. However, given the number of transactions possible in the modern company, automation is the best option.

With an audit trail, changes to any record are captured and time stamped with additional information, including operator or user name and why the record was changed. A system implemented to support audit trails also prevents unauthorized changes by ensuring role-based access and preventing users from directly updating the database. Such information, when collected, can provide evidence for an audit.

In a financial statement, variance, or the difference between the projected budget and the actual spend, of more than five percent will cause concern. To verify controls, auditors pull sample sizes as in internal testing. The auditor must determine the cause of any failures to see if it was an isolated incident. If errors are found in subsequent samples, the company must remedy the problem. An auditor has discretion to pass or fail an audit.

IT Audit

Preparing for and ensuring compliance may involve auditing existing IT infrastructure to identify inefficiencies, redundancies, and superfluous controls. Improvements can help to streamline reporting and auditing processes, and thereby increase productivity and reduce costs. It can also help firms to manage security risks more effectively and respond faster in the event of a breach.

The IT component of an SOX audit includes demonstrations of how it controls all electronic records and data. An audit can review:

- Access Controls: Physical access of servers, password controls, lockout screens, implementation of principle of least privilege (POLP)

- IT Security: Actions to prevent breaches

- Change Management: How you use change management logs to include and track new infrastructure, devices, and users

- Backup Procedures: Backup databases and store copies of important documents and content offsite or on the cloud

Consequences of Failing an Audit

At the worst, failing an audit can mean severe criminal penalties and at the least a loss of reputation. Failing an audit also tends to indicate lax internal controls, which may also translate into inefficiencies in day-to-day functions. The best response is to take any auditor suggestions seriously and act immediately to begin improving controls.

Companies that approach SOX compliance as a long-range initiative with good daily practice and a focus on critical areas can achieve success. In the long run, it’s better to spend consistent effort to get a good grade than to tire staff with unnecessary work in order to be outstanding for an audit.

Compliance Audit Preparation Checklist

Every organization has different audit requirements, but some needs are consistent across organizations. As a start, Laskowsky says it’s important to remember that not every device or file in an organization is subject to Sarbox. “Reduce scope so that you’re not trying to wrangle all IT assets and locations, so only those things that handle financial information should be identified, such as annual reports.”

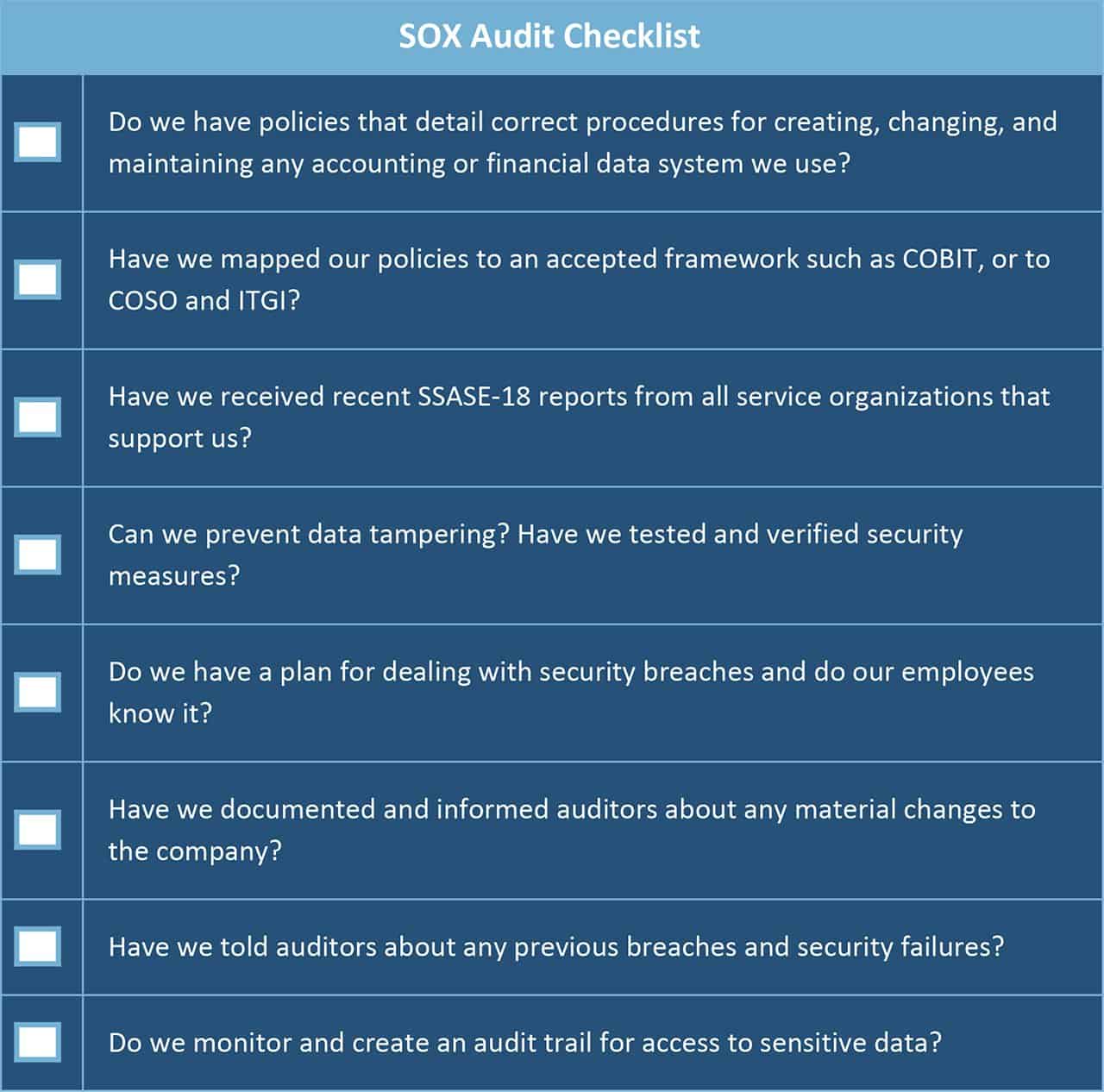

To understand requirements for your internal controls and audits, Laskowsky also suggests reading through the COBIT framework and mapping policies to the processes that apply to SOX. In addition, answer these questions beforehand to make your audit go smoothly and efficiently:

Working with a Sarbanes-Oxley Compliance Auditor

Although the auditor has the right to pass or fail a company, it’s worth the effort to find an auditor you can work with comfortably. Ask your industry peers to suggest auditors with experience in your vertical. Both Scott and Laskowsky suggest talking with the auditor. Someone in the industry understands “where the skeletons might lie,” and what requires compliance.

J-SOX and Governance Legislation in Other Countries

Inspired by Sarbox, other countries subsequently enacted their own financial governance legislation. Among others, countries with regulations include Canada with C-SOX, France with Loi sur la Sécurité Financière, and Japan, with J-SOX (formally known as the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act). As with other foreign companies, UK companies with U.S. listings must also adopt SOX compliance. Native-UK governance regulations include the Companies Act 2004 and 2006.

What Is a SOX Application?

Regulations such as the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS) concern confidentiality, but SOX focuses largely on integrity and prevention of tampering. Nevertheless, IT must provide an electronic audit trail, with non-repudiation (the ability to prove that a document or message was received and opened, or read). Records may need to be encrypted, compressed, and saved to a different file format.

For day-to-day operations, a network must prevent unauthorized users, even those with administrative rights to the system, from viewing regulated data. A system may also need to “mask” data for training and system testing purposes. It’s important to practice good network security hygiene, with proper physical and network access controls and monitoring through auditing of access and user activities to provide proper evidentiary trails. Compliance also includes safeguarding shared data.

Automation can help and also remove the burden of manual tests. Automated platforms allow rules to ensure only authorized access and monitor for potentially fraudulent behavior. Data classification tools with context sensitivity recognize and properly store secure information, especially PII, PHI, and social security numbers. Good implementations can be audit-ready at any time, ensuring integrity, policy management, and logging capability.

The advent of SOX unleashed a flood of software platforms for tracking and auditing. Companies spent millions, but the perceived need for expensive software changed as companies worked with SOX. “They found out it’s not all about IT and a new system,” says Laskowsky. “The point of Sarbanes Oxley is having controls, and what’s called compensating controls, so if you have a system that doesn’t quite cut the mustard when it comes to implementing security measures, you can always do something to compensate for that.”

When choosing software, you may also compare its capabilities to the tenets of the framework governing your organization, such as COBIT. Consider the following when selecting a program:

- It must comply with core regulatory requirements.

- The specs for intended use of software systems should correspond to your requirements.

- The software design and implementation plan must be documented to ensure throughout life of system that no errors throw system and content into non-compliance.

- The facility should also be audited for security.

Sarbox Talks: Key Definitions for Sarbanes-Oxley

The following are some important definitions used in compliance discussions.

- Compliance audit: A systematic review of financial records and business transactions for a company to ensure the firm complies with SOX guidelines.

- Independent auditor: An accountant who is unaffiliated with the company and who examines financial records and transactions. The auditor may be a certified public accountant (CPA) or chartered accountant (CA), but the accounting firm must be approved by the PCAOB to conduct SOX audits. Auditors may be self-employed or work for an accounting firm.

- Internal audit: A temporary or ongoing test that a firm conducts to test its own internal controls.

- Internal controls: The procedures and policies a firm uses to prevent, discover, and correct mistakes.

- Market capitalization: The value of a company, calculated by multiplying the price of stock by the total number of available shares.

- Material weakness: From the PCAOB Auditing Standard No. 5 Appendix A, “A material weakness is a deficiency, or a combination of deficiencies, in internal control over financial reporting, such that there is a reasonable possibility that a material misstatement of the company's annual or interim financial statements will not be prevented or detected on a timely basis.”

- Material misstatement: Information in a financial report that may harm investors.

- PII: Personal Identifying Data.

- PHI: Protected Health Information.

- Nonrepudiation: The guarantee that someone cannot deny having read, created, or signed something. In electronic communication, this takes effect through coded tags that prove, for example, that an email message has been opened.

- Service organization: Any third-party service company that provides financial or finance-related services. Service organizations originate in these types of industries: web hosting, registered investment advisors, medical billing, accounting, software as a service (SaaS) platforms, online fulfillment, data centers, and more.

- SAS 70 report: The predecessor to the SSAE-16/SSAE-18 report, the SAS-70 is an auditor’s attestation that reporting controls in a service organization are acceptable. During an annual Sarbanes-Oxley audit, a firm must collect and present a valid SSAE for each service organization they employ.

Summary of Sarbanes Oxley Act Titles

Title I Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB)

Title I creates the PCAOB to establish auditing guidelines and register trained accountancies for auditing, and to investigate disciplinary issues.

Title II Auditor Independence

This section focuses on establishing auditor independence and prohibiting auditors from performing bookkeeping, valuations, brokering, and other services for any firm they audit. It also specifies mandatory rotation from clients.

Title III Corporate Responsibility for Financial Reports

Firms must establish an independent audit committee. CEOs and CFOs must certify that they have reviewed financial reports and verify that they contain only true statements. Signing officers also certify that they have evaluated the controls within the previous ninety days, and report any problems with the internal controls, as well as any employee fraud. If reports must be revised, executives may need to forfeit bonuses and profits made through fraudulent statements.

Title IV Enhanced Financial Disclosures

Financial reports must be accurate and must not be deceptive or incorrect in the way information is presented. The section bans personal company loans to members of the C-suite. In annual reports, organizations must report on internal controls and auditing firms must comment on comprehensiveness of internal control structures. Information on material changes in the financial condition of the company must be disclosed without delay.

Title V Analyst Conflicts of Interest

One section protects analysts who prepare negative reports and prevents conflicts of interest that could result in biased reports.

Title VI Commission Resources and Authority

Defines SEC jurisdiction and power to supervise auditors and auditing firms.

Title VII Studies and Reports

Authorizes government studies and reports to support SOX enforcement and compliance.

Title VIII Corporate and Criminal Fraud Accountability and Criminal Penalties for Altering Documents

Describes fines and prison of up to 20 years for altering, destroying, mutilating, concealing, or falsifying records, documents or tangible objects with the intent to obstruct, impede, or influence a legal investigation. Also describes fines and sentences of up to 10 years for “any accountant who knowingly and wilfully violates the requirements of maintenance of all audit or review papers for a period of five years.”

Title IX White-Collar Crime Penalty Enhancements

Title IX raises penalties for crimes such as mail and wire fraud and violations of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). Section 906 details corporate responsibility for financial reports.

Title X Corporate Tax Returns

The single section requires that CEOs sign the corporate tax return.

Title XI Corporate Fraud and Accountability

Details expanded powers to prevent and investigate fraud and to increase penalties for violations. It also details punishment for retaliation against whistleblowers.

FAQ About SOX

What Is SOX compliance?

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (often shortened to SOX) is legislation passed by the U.S. Congress to protect shareholders and the general public from accounting errors and fraudulent practices in firms, and to improve the accuracy of corporate disclosures.

Why SOX compliance is required?

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, financial scandals in major US companies cost shareholders hundreds of millions of dollars. In some cases, poor financial practices resulted in the loss of entire retirement accounts for individuals. SOX enforces greater financial governance and transparency in public companies to ensure that investors better understand the risks involved in investment in any given stock. .

What is SOX control?

SOX concerns corporate governance and financial disclosure. Under the Sarbanes Oxley Act, all financial reports must include an Internal Controls Report. To comply with section 404 a SOX auditor must review controls, policies, and procedures.

Improve Sarbanes-Oxley Compliance with Smartsheet for IT & Ops

Empower your people to go above and beyond with a flexible platform designed to match the needs of your team — and adapt as those needs change.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.

Any articles, templates, or information provided by Smartsheet on the website are for reference only. While we strive to keep the information up to date and correct, we make no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability, or availability with respect to the website or the information, articles, templates, or related graphics contained on the website. Any reliance you place on such information is therefore strictly at your own risk.

These templates are provided as samples only. These templates are in no way meant as legal or compliance advice. Users of these templates must determine what information is necessary and needed to accomplish their objectives.